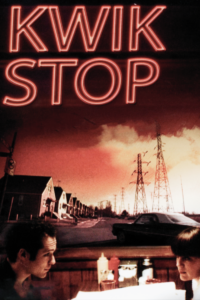

Kwik Stop was released in 2001 but, despite winning several film festival awards, didn’t get much attention or distribution. It’s recently been added to Amazon Prime, so hopefully it will get a wider audience, which it truly deserves. A Slate article by Charles Taylor argues that the lack of fanfare around Kwik Stop reveals everything that’s wrong with the movie industry. This article is from almost 10 years ago; if anything, things are worse today.

Michael Gilio wrote, directed, and is one of the stars of Kwik Stop, a hard to label micro-budget film that doesn’t often do what we expect. Set in a dismal, generic American landscape that appears to be somewhere in the Midwest.

It starts as a young guy who calls himself Lucky (Gilio) drives up to a convenience store in a classic car. Between his car and haircut, he looks like a James Dean character. After doing some petty shoplifting, he’s confronted by Didik (Lara Phillips), a teen who’s anxious to leave town. She threatens to tell a nearby cop about Lucky’s crimes if he doesn’t give her a ride. He plans to drive to Hollywood to become an actor. Didi wants to tag along.

With this start, Kwik Stop looks at first to be a road movie, possibly the violent kind along the lines of Bonnie and Clyde or Badlands. However, neither of these characters is quite capable of acting out such extreme actions. They are limited by a kind of circumstantial and existentialist quicksand that prevents them from getting too far.

What follows are some mild spoilers, though Kwik Stop is not a plot-driven movie, so there’s not really much to spoil.

Lucky and Didi have a series of fairly absurd misadventures involving burglaries that result in Didi getting sent to a juvenile detention center. Lucky then concocts an absurd scheme to break her out, recruiting his ex-girlfriend to assist. This sequence of events is part of what’s refreshing about the movie. Your first instinct may to think, “this is too ridiculous; no one would do anything like that. But when you think about it, it’s so ridiculous that it seems like it could be true. It’s actually too ridiculous to fit into a formula novel or screenplay.

Along with Lucky and Didi, a depressed alcoholic named Emil (Rich Komenich) gets sucked into Didi’s chaotic life. He’s a sad sack character who proves to be more complicated than he first appears.

To appreciate Kwik Stop, you need to take a step back from the characters and understand that no one really knows what they’re doing. They are oddly believable as people who are making everything up from one moment to the next.

As the aforementioned Slate article points out, some of Kwik Stop‘s absurdity is reminiscent of early Jim Jarmusch films such as Stranger than Paradise and Down By Law. Later mumblecore movies of the early 2000s also have some similarities. However, Gilio has a distinct style of his own. Jarmusch’s characters, often seem like they are in a perpetual existentialist fog. By contrast, Lucky and Didi actually seem to believe they are headed somewhere; it’s just that their plans and actions are so confused and self-defeating that they have no chance of achieving their goals.

Kwik Stop is the kind of low key, unpredictable indie movie that’s all too rare these days. It’s currently streaming on Amazon Prime, FreeVee, Apple TV, and other services.